Households and clinics improvise amid chronic blackouts

Myanmar is rapidly embracing small-scale solar power as civil war, sanctions and fuel shortages push the country’s electricity system to the brink. After Thailand cut power exports across the western border this year to squeeze criminal scam networks, communities in towns such as Myawaddy saw already unreliable supply deteriorate further. Hospitals, clinics and local government offices began installing rooftop panels to keep essential services running, while small businesses turned to solar to preserve food stocks and run payment systems. Residents interviewed by local intermediaries describe a sharp shift: where diesel generators once dominated, three out of four households in some areas now rely in part on solar panels and batteries.

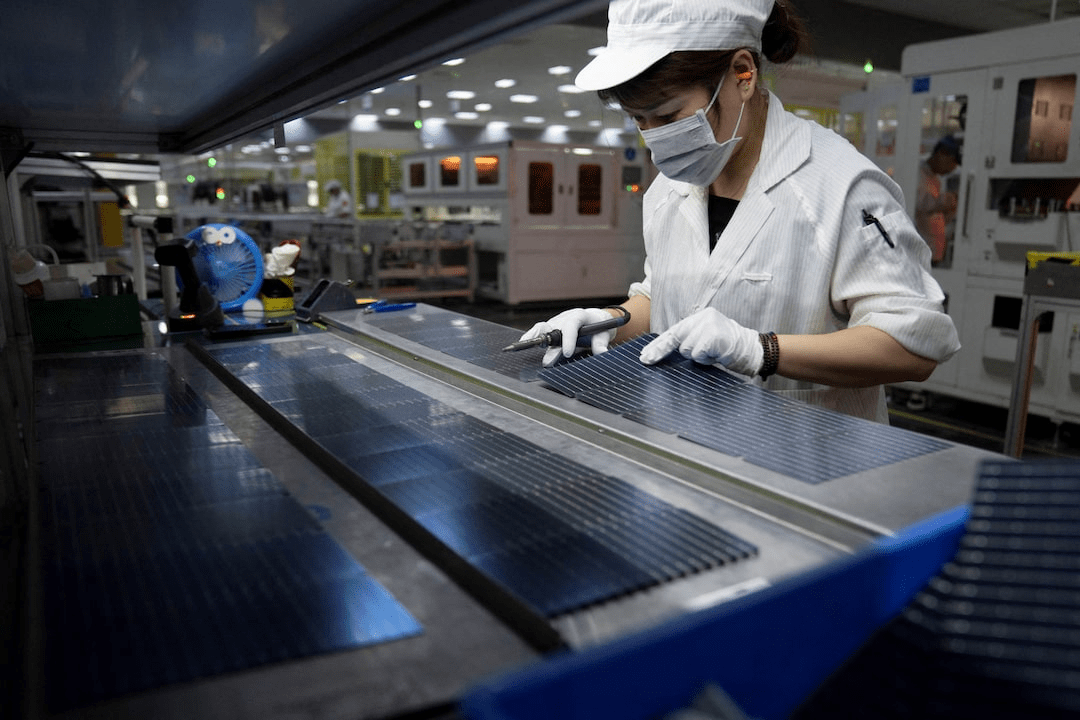

The World Bank estimates Myanmar’s operating power capacity fell back to around 2015 levels by 2024, as conflict, lack of foreign currency and sanctions crippled maintenance of gas-fired plants and transmission lines. A shortage of natural gas—the country’s main fuel for large power stations—has forced the junta to cut liquefied natural gas imports, while attacks on infrastructure have further destabilised the grid. In this vacuum, cheap panels from Chinese manufacturers have poured in, with imports more than doubling in the first nine months of 2025 compared with pre-pandemic levels. For many households, a basic solar-plus-battery kit costing under $1,000 is still expensive but preferable to a small diesel generator that can cost several times more once fuel is included.

Necessity, not climate ambition, drives the solar surge

Analysts say Myanmar is a striking example of how fragile grids in lower- and lower-middle-income countries are pushing ordinary consumers to become their own power providers. Similar trends are emerging in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Iraq and Afghanistan, where unreliable utilities and rising tariffs are nudging families and businesses toward rooftop solutions. In Myanmar’s case, residents stress that the shift is not driven by climate policy or green branding. For them, solar is simply the cheapest and most practical way to keep the lights on in a war-torn state where government institutions are either absent or distrusted.

The boom carries broader implications for energy planning. As more homes and businesses go partially off-grid, utilities can lose higher-paying customers, leaving fewer people to shoulder the cost of maintaining lines and power plants. That may force price hikes on those who remain dependent on the grid, deepening inequality between households that can afford solar kits and those that cannot. At the same time, the spread of small systems complicates efforts to forecast fuel demand and manage voltage on already stressed networks. For Myanmar, however, the immediate priority is survival. In the absence of political stability and large-scale investment, a patchwork of rooftop panels, storage batteries and improvised wiring has become the backbone of everyday life, even if it offers only a few hours of power each day.

TPW DESK

TPW DESK