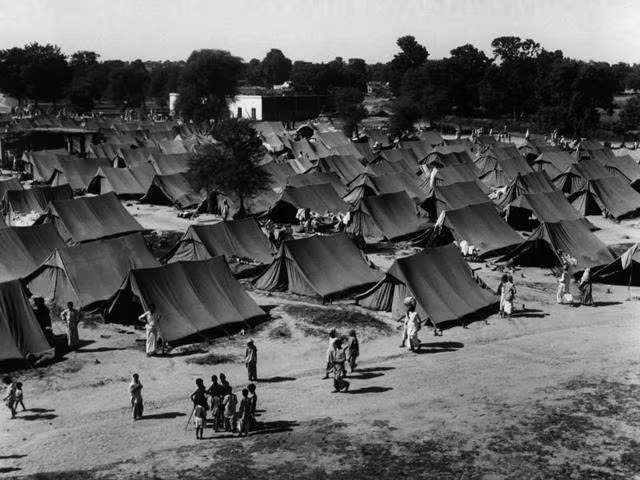

Refugee is a well-known word worldwide. Every moment, someone somewhere in the world is becoming a refugee. Some on their own choice, some forced. Among the myriad problems of civilization and state systems, the refugee issue is one of them. Just as there are no permanent solutions to any social science problems, there is no permanent solution to the refugee problem yet.

There has not been much opportunity to see refugees from different parts of the world repeatedly. I had the opportunity to meet a few refugees from the Middle East in Europe. I have known some Afghan refugees in America and India. I have also had the opportunity to know some refugees in Malaysia. There have been few interactions with Indian refugees from several generations in Thailand or Singapore, and with Burmese refugees.

However, the most opportunities have been to know those who became refugees in India from East Bengal and present-day Bangladesh. Also, those who came as refugees to Bangladesh from Pakistan.

The third generation of these two classes of refugees is now ongoing. I had the opportunity to see the first and second generations. Now I am getting the opportunity to see the third generation as well. Additionally, there is an opportunity to see the second generation of another class of refugees, the Rohingyas who came to Bangladesh in the 1970s.

Those who came to East Bengal from India, much of their first generation, have left with memories of their homeland. Their constant talk was about their “makan” (house). And those who went to India from East Bengal, their constant talk was about their “mati” (land).

Fewer people came from India to East Bengal. On the other hand, a larger number left East Bengal. Therefore, from 1947 to the 1960s, those who came to East Bengal from India had relatively more opportunities for support from the government of East Bengal or later East Pakistan, compared to those who entered various states of India from East Bengal.

Due to more people leaving East Bengal, many houses and business establishments remained vacant. As a result, those who came here losing everything and initially stayed in camps were quickly rehabilitated well.

In Comrade Toaha’s autobiography, it is seen that the government’s policy was that those who left one house did not leave just one house, but also left behind wealth. Therefore, in exchange for one house, two houses were allocated for them. Similarly, those who left one shop were allocated two shops. Comrade Toaha writes that at one stage some even took the opportunity. Even if they had one shop there, they claimed to have two shops here. Thus, they received four shops.

But their luck did not last long. Because every part of their lives was stained with the blood of riots and memories of leaving their own home. Therefore, they considered Pakistan as their own in contrast to these memories. Exploiting this weakness, many brutal acts were carried out by them in the name of protecting Pakistan in 1971.

This means that a large part of them have to return to refugee camps, which became known as Geneva Camp. Their brand name then changed from refugee to stranded Pakistani. As a journalist, as an acquaintance, and out of an interest in Urdu literature, I had the opportunity to closely observe the lives of these stranded Pakistanis, which is like a different kind of novel. To bring out such a novel, it would require a powerful novelist like Bankim. As Syed Mujtaba Ali wrote, true literature about Bangladesh’s Liberation War will only be created when an epic is written, because through this event, every person in the country has become a character in this epic. And according to Mujtaba Ali, we will have to wait for another Michael (referring to Michael Madhusudan Dutt) to be born to write that epic.

In contrast to those coming to East Bengal from India, more refugees entered various provinces of India, including Assam, Tripura, and Meghalaya, especially West Bengal, from East Bengal.

There were not enough empty houses or business establishments in West Bengal to accommodate them. Therefore, much of their lives descended into inhuman conditions. School teachers even accepted beginning with bowls in hand.

However, compared to those who came to East Bengal from India, a significant portion of those who went to India from East Bengal had another valuable asset—education. High-caste Hindus predominantly held this educational asset. With the strength of this education, by the time the second generation arrived, a large portion of the upper-caste Hindu refugees had established themselves fairly well in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, South India, and most notably, Kolkata.

Perhaps the overall refugee situation could have been established even better across West Bengal and India if the attempt by West Bengal’s then Chief Minister Bidhan Roy to form a province including West Bengal and Bihar had not failed in the face of leftist movements. There’s no point in blaming the leftists here because history will at least award them one prize for their politics in this subcontinent—that they never made any correct decisions.

However, discussing that would divert the writing in another direction. But from the documents I have had the opportunity to review about the management of refugees in West Bengal, it is clear that in the politics dominated by North Indian politicians, the problem of refugees from Northeast India was not well understood. Whatever efforts were made were largely due to Bidhan Roy’s individual efforts. Therefore, while the Indian government was relatively successful with Punjabi and Sindhi refugees, it was not as successful with Bengali refugees. As a result, the lower caste Bengali refugees fell into even greater trouble. These lower caste people were primarily those from river or coastal areas. Those involved in river or land work could not adapt elsewhere in the same way. They viewed the Andaman Islands as Kalapani (a term denoting a grim and distant penal colony) or a terrifying death journey.

Thus, like the stranded Pakistanis in Bangladesh, the lives of lower-caste Hindu refugees who went to India from East Bengal became another dreadful novel. To narrate this, we would need to reincarnate Bankim again. This refugee stream is ongoing and not ending.

Even writing about why it isn’t ending would divert the writing in another direction. Moreover, the psychological aspects of the stranded Pakistanis or the lower caste Hindu refugees who went to India, and their suffering, could fill books; it’s not possible to express them in a column.

However, the truth is that with the evolution of time, these issues have now gone into hiding and will go further into obscurity. This is the nature of time. Perhaps hundreds of years later, just as African American arts in America—dance, music, paintings—sometimes remind us that they are African American despite being American, similarly, hundreds of years later, when an Eastern Bengal melody like Bhatiyali or Bhaoaiya or Kirtan mixes with North Indian or South Indian tunes to create something new, someone might remember that it is from East Bengal.

*Moreover, the current reality of the world is so harsh that by the third generation, the river takes a nearly complete turn. That turn is found in the bend of the Teesta.*

Through two gates of India’s Teesta Barrage, a thin stream of murky water flows towards Bangladesh, pushing a large sandbar in a meandering path. This sandbar has now become an island-like spot for afternoon outings. As a result, large umbrellas with tables underneath have been set up on and beside the river bank like a seaside resort, along with makeshift restaurants where many people come from Siliguri to spend a pleasant evening.

Arriving there under the scorching summer sun, everything appeared empty. The murky water of the Teesta flowing out of the barrage wound its way towards Bangladesh’s Teesta River. In the distance, Bangladesh’s green forests were like a border line. On one side, the nearly dead Teesta River, and above it, the monstrous barrage. In front, the sandbar of the Teesta’s bed, now a recreational area for travelers. And there’s more, but not here.

As I pondered these scenes with a troubled mind and thought about drawing lines for the future, I was startled by a sweet voice. A thirteen or fourteen-year-old boy sitting in the shade of the bushes on the riverbank approached and asked, “Do you want to go to the sandbar?”

“How will we go?” I asked.

“There, I have a boat. I’ll bring it,” he replied.

“Won’t such a small boat sink in the river?”

With a sweet smile, he said, “How will it sink? There’s no water in the river for the boat to sink.”

“No water in such a big river?”

“Come with me. I’ll show you with the paddle how little water there is.”

“I’m afraid to get on such a small boat.”

“I’ll help you on. Don’t be afraid. You stand there, and I’ll bring the boat.”

He helped me onto the boat, and under the scorching midday sun and 36-degree Celsius temperature, we went to the sandbar. Although the sandbar was clearly visible from the shore, it felt like I was being taken into a different realm, reminiscent of a scene from Kapalkundala.

After returning from the sandbar and stepping off the boat with his help, I asked where his house was. He pointed to a broken, hidden house beside the river road, surrounded by a few trees, and said that was his home.

I learned he was in eighth grade at a local school and did this work in the mornings, evenings, and during holidays.

When I asked what his father did, he pointed to the Teesta and said, “Catches fish in this river.”

“What kind of fish does he catch?”

He lowered his head slightly and said, “Due to the heavy silt from Sikkim during this year’s flood, both the crops and the fish have decreased.”

“Do you know which country is on the other side of the green line there?” I asked.

He shook his head and answered, “No, I don’t know.”

“Have you heard of Bangladesh?”

He said, “Yes, I have heard of it. My grandfather said his home was in Bangladesh.”

“Where in Bangladesh?”

“No one knows since my grandfather passed away.”

“Don’t you want to know?”

No response. Rather, his expression indicated he didn’t want to answer any more questions, perhaps due to the whims of a teenage mind.

“Do you know anything else about Bangladesh?”

Shaking his head, he said, “No.”

I then offered, “I am from Bangladesh. I came from there.”

No interest was visible in him about this. There was no change in his expression. Yet, in the sixties, when first-generation refugees in Madhya Pradesh heard I was from East Pakistan, they surrounded me, took me to their tents, and fed me whatever they had. Remembering that, I looked at him again and asked, “What is your name?”

In a very indifferent voice, he said, “Buddhadeb Sarkar.”

“Whose house is that away from yours?”

Again, with irritation, he replied, “I don’t know exactly.”

Meanwhile, I had taken a few pictures of Buddhadeb.

As I paid for the boat rental and walked towards the car, I reflected that by the third generation, the lower-caste Hindu refugees from East Bengal had forgotten their ancestral land.

Yet, despite this, he still seemed like a refugee to me. Like all refugees in the world, he appeared somewhat solitary. He didn’t even know whose house the distant one belonged to, nor did he care.

In other words, even though he has completely forgotten his ancestors’ land by this generation, he will not be able to escape many of the typical symptoms of being a refugee. He will have fewer companions. And this loneliness, if nothing else, will shorten his lifespan. He might live longer than the first generation, but even so, his lifespan will be shorter than the national average. Like refugees or immigrants worldwide. Although it is said that the average lifespan is shorter for the first generation, reality is even harsher.

As I pondered all this, I looked back at him again. For some reason, I felt there was an expression of acceptance on his face. In other words, he too is another resilient Buddhadeb.

The author is a national award-winning journalist and editor of Sarakhon and The Present World.