When Dr. Zafarullah took the initiative to formulate a drug policy during Ershad’s regime in Bangladesh, our journalism largely mirrored this policy because Ershad was a military ruler, and everything about him was opposed. The exception, however, was meeting Dr. Zafarullah. He discussed the necessity of the drug policy in very simple language. From his discussions and after thoroughly studying the drug policy, I realized with my limited intellect that this path would lead to the development of the pharmaceutical industry in Bangladesh.

It would be unjust not to mention another individual, Awami League leader Mohaimen Bhai. Whenever I visited his Pioneer Press for printing, we would discuss various issues, and he would encourage these conversations. He was also a proponent of industrializing the country, favoring industries that minimized land wastage while employing many workers directly and indirectly. He believed that these industries should eventually become export-oriented and advised me to write in favor of the drug policy

At that time, I was an assistant editor of a B-category daily in Dhaka. I wrote a column supporting the drug policy. Since the daily had indirect connections with a minister from Ershad’s government, many assumed I wrote the column as a job security. However, I was pleased to receive gratitude from Dr. Kamaluddin, the founder of Nuclear Medicine at PG Medical College & Hospital, and Mostafizur Sir of Nutrition Science at the University of Dhaka. Long before this, their affection had given me the opportunity to write extensively about the necessity of iodized salt. Both appreciated my stance on the drug policy, saying it was courageous to write in its favor.

As a modest journalist, I reflect on the implementation of the drug policy when 80% of drugs were imported. Now, 97% of the necessary drugs are produced domestically, and Bangladeshi drugs are exported to 113 countries. Although I played no direct role in this achievement, I feel a small sense of pride as a journalist, knowing I recognized the policy’s potential early on.

Bangladesh’s pharmaceutical industry has firmly established itself and continues to advance with support from all stakeholders. However, history shows that when a particular industry thrives, related industries in the country also begin to flourish, necessitating governmental support. For instance, when the real estate business boomed, many local fittings companies emerged. The government could have supported these industries more by restricting imports of foreign house fittings, thus fostering domestic growth. Considering the indirect benefits of employment and domestic development, the government could have raised import duties, enforced quality checks, and implemented anti-dumping measures. This would not only have supported our industries but also prevented the influx of low-quality, tax-evading imports.

The Need for a Self-Sufficient Pesticide Industry in Bangladesh

The pesticide industry, closely related to the pharmaceutical sector within the realm of drugs, is crucial for Bangladesh for two significant reasons. Firstly, to boost the country’s agricultural production, and secondly, to protect its population from insect-borne diseases and prevent related fatalities.

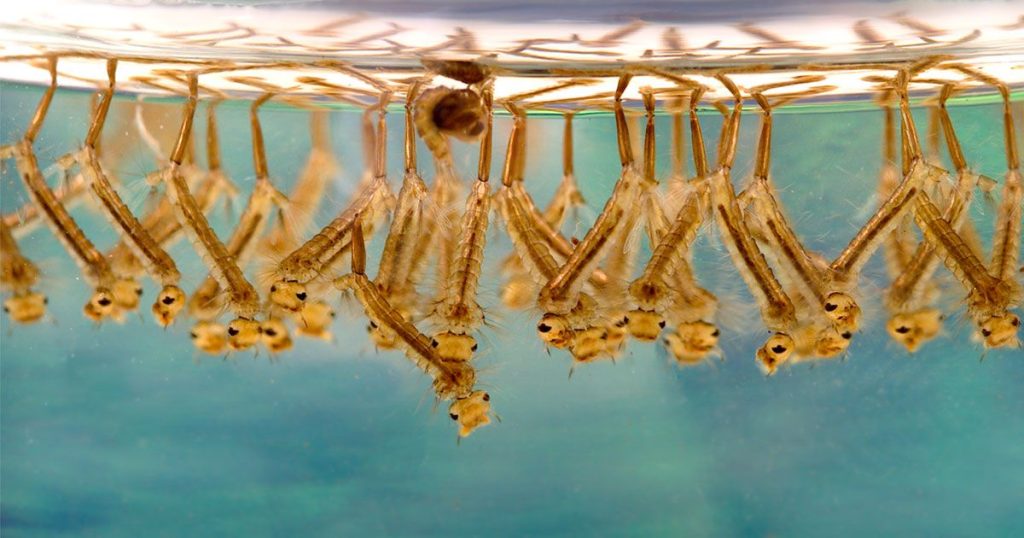

Bangladesh has not yet achieved a 100% malaria-free status. Malaria-carrying mosquitoes are still prevalent, particularly in the hilly regions where they breed sporadically. Alongside them are the vectors for kala-azar. Furthermore, dengue—commonly referred to as “dengue” in local terminology—has been a persistent issue in South Asia and Southeast Asia since the 18th century. Historical accounts suggest that even earlier, certain fatalities accompanied by fever symptoms were likely due to dengue. Environmentalists and entomologists note that the climate of South Asia and Southeast Asia is conducive to the breeding of dengue mosquitoes. Thus, for geographical reasons, Bangladesh must actively eradicate these mosquitoes during their breeding season to safeguard its populace.

It is also important to note the expansion of dengue beyond urban centers to rural areas in Southeast Asia and East Asia. This trend is beginning in Bangladesh and is expected to extend to rural villages, mirroring other regions. The transformation of rural areas into suburban or urban fringe areas incorporates urban elements into village life, creating environments suitable for dengue mosquito breeding—even if these areas remain governed as unions rather than city corporations. Consequently, there will be a future need for environmentally friendly yet effective dengue mosquito-killing pesticides before each breeding season.

If the government remains dependent on imports for these pesticides, two crucial assurances cannot be guaranteed. First, the effectiveness of the pesticides against dengue mosquitoes, and second, their environmental friendliness. Dependence on imports, which involves a high number of importers and various importation methods, means the government cannot exercise complete control. This raises concerns about both the timely arrival and the standard quality of foreign pesticides.

The Urgent Need for a Domestic Pesticide Policy in Dhaka

Often, the mayors of Dhaka face severe criticism due to dengue outbreaks. Upon investigation, it is revealed that the ineffectiveness of the pesticides is due to deception by the importers. Consequently, even after spraying, the mosquitoes continue to thrive. Additionally, these importers cause delays in pesticide delivery.

As urbanization increases, it is essential to protect various facilities such as habitats, hospitals, hotels, schools, and transportation hubs like rail and bus stations, airports, and seaports from various insects, not just mosquitoes. Simply put, regular pest control has become as crucial as any of the other ten essential tasks of urban living. Hence, access to good quality, low-cost pesticides is now indispensable for the country.

Furthermore, agricultural production is a primary concern. It is a misconception that agricultural output can be increased without the aid of fertilizers and pesticides. Although Bangladesh once achieved self-sufficiency in rice production, the ongoing reduction in agricultural land and the increasing population pose significant challenges. Over the next five to seven years, a large number of young men and women will start families, necessitating new housing and further reducing available farmland. In this scenario, enhancing agricultural production is imperative.

Bangladesh is actively working to boost its agricultural output, notably through diversifying its agricultural products. The country is not limited to producing just rice, wheat, or jute; it is striving to cultivate a wide array of fruits, vegetables, and even spices globally. Significant progress has been made in the production of fruits and vegetables. However, to elevate this to the highest level, it is essential to keep all crops, from fruits to grains like wheat, corn, millet, and barley, pest-free. This is particularly crucial as a large portion of fruits and vegetables are consumed raw or minimally cooked, necessitating the use of environmentally friendly pesticides.

In the 1990s, Abul Mal Abdul Muhith, a former Finance Minister, worked on a World Bank project analyzing the foreign pesticides used on vegetables in Bangladesh. His findings were so alarming that he refrained from eating raw cucumbers and advised those close to him to do the same. The imported pesticides used in cucumbers remained in the cucumbers without degradation, implying that consuming these cucumbers was akin to ingesting pesticides directly.

Given the health, environmental, and food production challenges, Bangladesh urgently needs to develop a pesticide production policy similar to its drug policy. The primary goal should be to emulate the success in medicine, aiming for Bangladesh to produce 97% to 100% of its needed pesticides. Eventually, like its pharmaceuticals, Bangladesh could export pesticides to over 113 countries.

Addressing Obstacles in the Development of Bangladesh’s Pesticide Industry

At present, a critical issue in the development of Bangladesh’s pesticide industry is the same barrier that impeded the growth of the country’s house fittings industries, namely, wholesale imports. Currently, only a 5% duty is levied on these imports. In contrast, neighboring India increased its pesticide import duty from 10% to 15% in their last budget, with additional taxes bringing the total duty to about 18%. However, according to discussions with a prominent economic reporter from India, the actual duty paid by importers can exceed 22%, along with numerous other hurdles.

In Bangladesh, the situation is the opposite. Importers face only a 5% duty and no significant additional obstacles. Meanwhile, local producers face numerous challenges. For instance, their sources of raw materials are restricted and not open, which hampers their ability to source quality raw materials at competitive prices. One of the fundamental principles of industrialization is to provide producers with open access to raw materials.

Another issue is the ease of importing raw materials. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, raw materials are tested in factories rather than at ports to avoid the high costs associated with time demurrage. Conversely, pesticide production in Bangladesh is hindered by mandatory field testing, a requirement that lacks clear justification and is difficult for journalists to analyze or explain. Nevertheless, it can be said that formulating a pesticide industrial policy similar to the drug policy—by involving real experts and stakeholders—could remove this barrier.

Furthermore, like India, Bangladesh should consider imposing higher duties on pesticide imports to protect and foster the domestic industry.

Over the past fifteen years, significant infrastructure has been developed in Bangladesh to support economic growth. However, the full benefits of these investments cannot be realized without robust industrialization. Not only is industrialization essential for straightening the economy’s backbone, but it is also crucial for providing employment to the burgeoning young workforce. A large segment of the population is currently engaged in agriculture, often under conditions resembling semi-unemployment. Real economic development and the dynamism that comes with it require the creation of full-time jobs, which can only be achieved through industrialization. The pesticide industry represents just one sector where attention is needed; other industries must also be considered to ensure comprehensive economic growth and job creation.

Writer: Swadesh Roy, national award-winning journalist and editor of Sarkhon and The Present World.