Scientists warn “relentless” carbon rise keeps world off 1.5°C path

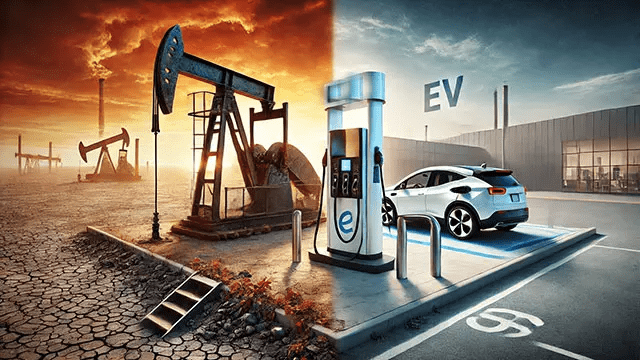

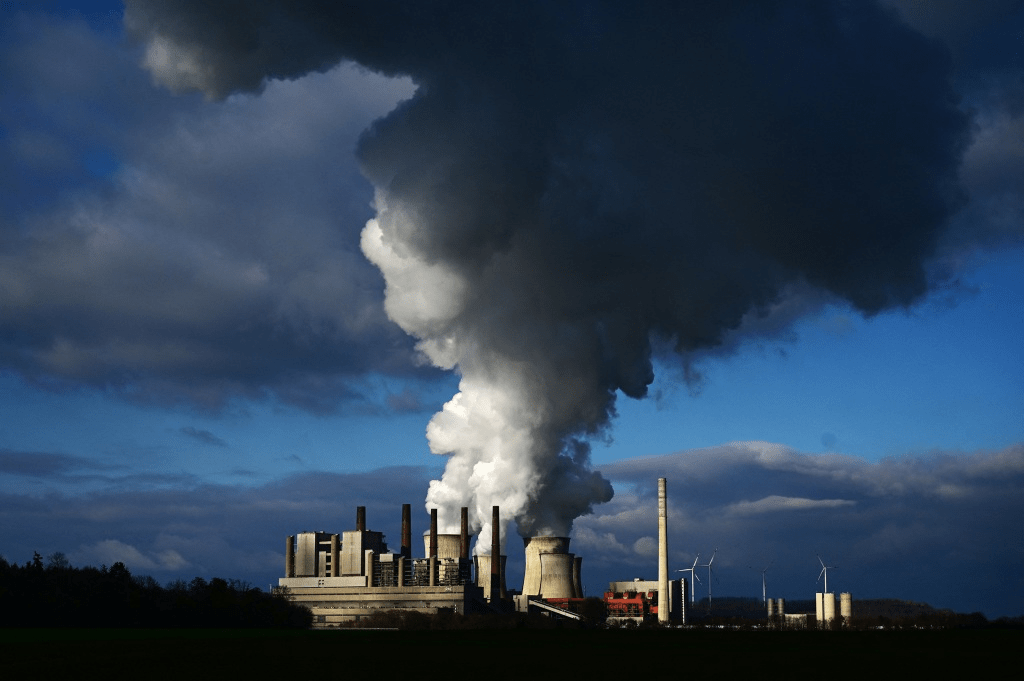

Global emissions from burning coal, oil and gas are on track to rise by about 1.1% in 2025, marking the second straight year of increase and slightly weakening hopes that climate action could soon force a peak. The latest estimates, unveiled by the Global Carbon Project at United Nations climate talks in Belém, Brazil, show fossil-fuel pollution hitting a record level even as clean energy deployment accelerates. Researchers calculate that human activity is adding around 42 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere this year, the equivalent of nearly 2.7 million pounds of CO₂ every second. They describe the trend as “relentless” and warn that without a rapid reversal, the chances of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels will continue to shrink.

The headline figure hides important regional differences. Emissions in some advanced economies have declined as coal plants close and renewables gain ground, with around 35 countries managing to cut fossil-fuel pollution while still growing their economies. But these gains are being offset by increases elsewhere, including a roughly 2% rise in the United States, where recent policy rollbacks have slowed the pace of decarbonisation. Aviation-related emissions have jumped by nearly 7% as international travel rebounds, further complicating efforts to stabilise the global carbon budget. Land-use changes tell a more mixed story: a significant drop in deforestation and other land-based emissions has largely balanced out the fossil-fuel increase, leaving total human-caused emissions roughly flat compared with 2024.

A separate analysis by Climate Action Tracker, also released on the sidelines of COP30, paints a sobering picture of where current policies lead. If governments implement only the measures already on the books, the world is heading toward roughly 2.6°C of warming, far above the Paris Agreement’s safer thresholds. Even if every country fully honours its latest pledges, the trajectory would fall only to about 2.2°C, still enough to unleash more extreme heat, sea-level rise and ecosystem damage. The authors say recent moves by the U.S. administration to ease some climate regulations and expand fossil fuel production have nudged their projections in the wrong direction.

Negotiators in Belém now face a difficult balancing act: maintaining political momentum for stronger climate commitments while acknowledging that emissions are still rising. Some delegates argue that the modest 1.1% increase shows the world is edging closer to a plateau before declines, especially as China’s emissions show signs of nearing a peak thanks to massive renewable deployments. Others counter that any rise, however small, is unacceptable given the narrowing carbon budget and the escalating impacts already being felt in vulnerable regions. With climate-fuelled floods, heatwaves and storms fresh in many leaders’ minds, the data has sharpened calls for a global agreement to phase down fossil fuel production, not just consumption.

Finance remains another sticking point. Developing countries point out that they are being asked to pursue low-carbon growth while still struggling with debt, inflation and climate-linked disasters. They are pressing richer nations to deliver on long-promised funding for adaptation and loss-and-damage support, arguing that without predictable finance, it will be harder to avoid locking in new coal and gas infrastructure. Scientists behind the emissions report stress that the technology to bend the curve already exists—from renewables and grid upgrades to efficiency and reforestation—but warn that political will and financial flows are lagging behind what the physics of the climate system demands.

TPW DESK

TPW DESK